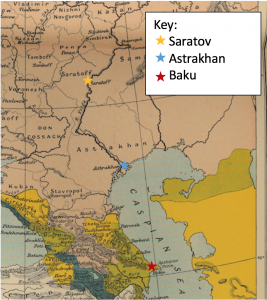

Cholera entered Russia along the coast of the Caspian Sea in mid-May 1892; historians believe that it is impossible to precisely pinpoint where the outbreak first began in Russia, and seem to even struggle to agree on which specific side of the Sea the bacteria entered Russia. Some argue that it was first found in Baku, on the western coast in the southern Caucus, whereas others believe that that it began in Astrabad (which was part of the Persian Empire along the southeastern corner of the Caspian Sea) and may have infected nearby Russian cities such as Askhabad before crossing the Caspian Sea.1

EDITED: Map of the Caspian Sea Region and Caucuses, indicating Major Cholera Cities Referenced1

EDITED: Map of the Caspian Sea Region and Caucuses, indicating Major Cholera Cities Referenced1

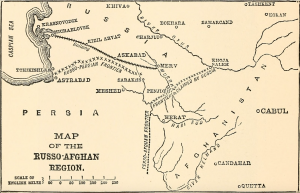

Map of the Russo-Afghan Region2

Map of the Russo-Afghan Region2

Regardless of where the epidemic began, the spread is undeniable. Once it was officially announced that cholera had been found in Baku, people began to flee from the city to surrounding regions of the Russian Empire. They did this through various modes of transportation, including on large (and ill-regulated) passenger ships which ferried overcrowded boats of people across the sea to different port cities, as well as on foot.2

Notably, the relatively recently opened Transcaspian and Transcaucasus Railways served as major modes of transportation out of infected areas.3 As Russians fled the disease, packed tightly into passenger cars, they spread cholera both westward toward the Black Sea, and eastward toward Tashkent , the capital of Russian Turkestan, as well as in all other directions by ship and by foot.4

The cholera outbreak represented a unique opportunity for the Russian Empire; it was initially viewed as a way for Russians to assert their modernity, and to prove, through effective management and containment, that they had reached the same level of scientific advancement as Europe.5 Russians hoped to demonstrate their grasp of modern medicine, which included the world’s rudimentary understanding of the cholera bacteria, as Robert Koch had isolated Vibrio cholerae as the causative agent about a decade prior.

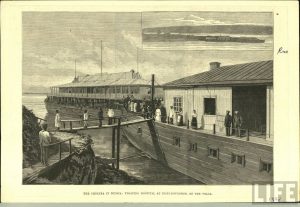

“Floating hospital being used to treat cholera patients at Nijni-Novgorod on the Volga River, Russia, 1892”3

“Floating hospital being used to treat cholera patients at Nijni-Novgorod on the Volga River, Russia, 1892”3

Unfortunately, however, the epidemic largely had the opposite effect. Many fault lines in Russia were exposed, such as insufficient medical technology, ineffective bureaucracy, and deep rooted mistrust between the people and public officials.6 The cholera epidemic became a “marker of backwardness in comparison with the rest of Europe.”7 When the epidemic was finally over, more than 260,000 Russians were dead (Henze 2011).8

Most importantly, people reacted negatively to the quarantine and cholera-related sanctions that local governments enacted. Just as cholera epidemics had sparked riots throughout Europe at the beginning of the century, so too did Russians experience riots toward the end. However, the cause of the riots went beyond dissatisfaction with how the government was handling the epidemic and were not universal. Overall, anxieties surrounding cholera functioned as a spark that revealed tensions between middle-class Russians and those that they considered to be outsiders, including medical elites, and colonized Muslims.