The tensions that cholera exposed in Tashkent were between Russian colonizers as the insiders, and the Muslim peoples that they colonized. Tashkent, the present day capital of Uzbekistan, became a part of the Russian Empire through military conquest thirty years prior. At the time of the cholera outbreak, the city was very much divided between a ‘Russian’ and and ‘Asiatic’ quarter, and tensions between the two groups were prevalent.1

Even before cholera arrived, Russians viewed the Central Asian Muslims they were colonizing as uncivilized and dirty–therefore, the Russian elite believed that they would be able to display their superiority over those they had colonized by “civilizing” them through the cholera epidemic.2

When word got out that cholera had reached Tashkent on June 7, 1892, discourse that framed Muslims as dirty became even more prevalent, as throughout the nineteenth century, elite Russians had juxtaposed the populations they colonized as “bearers of dirt and disease, against the clean and healthy European.”3 In this way, the concept of ‘dirtiness’ became a stand-in idea to invoke race without explicit reference; while Russians viewed ‘race’ as fixed, framing the imposed hierarchy around ‘dirtiness’ and ‘cleanliness’ implied the ability of Russians to “civilize” those that they colonized by enforcing western hygiene practices.4

Modern Map of Central Asia1

Modern Map of Central Asia1

Furthermore, Muslims were perceived throughout the Russian Empire (and the Western World) as “fatalistic.” For example, Kazanskii wrote that during the 1872 cholera epidemic “Muslims were left to die in the streets, as evidence of their ‘indifference towards matters of life or death.'”5 Further adding to the belief that Muslims were fatalistic, Westerners believed that they categorically refused medical treatment, and would participate in burial rituals with their dead which would further spread outbreaks of cholera.6

Although cholera arrived in Tashkent through a poor Russian woman on the outskirts of the Russian quarter, government officials focused their response on creating new regulations for the Asiatic quarter. While quarantine was enforced throughout the entire city, forbidding travel outside of Tashkent’s suburbs, the Russian general in charge of controlling the outbreak focused the medical committee on Asiatic Tashkent. For example, those living in the Asiatic district wee required to report any resident who became sick with any illness to Russian medical clinics, cholera stations, or the police, at which time they were removed from the home, which violated local cultural practices surrounding the ill and the dead, which upset many Muslim residents.7 As more and more people died, and as anger surrounding the treatment of corpses intensified, rumors began to spread that the Russian government had purposefully infected the Central Asian population of Tashkent, and people began to bribe Russian officials to allow them to care for sick loved ones at home, or to change the cause of death on official documents to allow the dead to be buried in family graves.8

Finally, on June 23, 1892, Muslim residents of the Asian Quarter went into the Russian side of the city, looking for one of their leaders who had gone to meet with Russian officials, in the hopes that regulations for burying the dead had changed.9 At first, Russians settlers calmly watched this protest at the main legislative building, as they did not feel as though the social structure was being threatened.

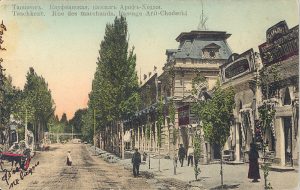

The Streets of Tashkent, circa 19102

The Streets of Tashkent, circa 19102

However, when the crowd failed to find the Russian official who they hoped to persuade to return power to Central Asian officials, they began to disperse. At this time, some unarmed Russian soldiers arrived at the legislative building. The presence of soldiers meant that the Russian settlers believed that they were witnessing a direct challenge to the social order they had imposed; as a result, Russian soldiers and settlers alike began to employ violent tactics to force the Muslims back to the Asian quarter, in effect using “violence to enforce the boundary between Russian and Central Asian, between colonizer and colonized.”10 The Russians continued on to brutally beat Asian shopkeepers and those who retreated; it is estimated that between eighty and one hundred Asians were killed as a result.

In the end, the Russians were not held accountable for the violence that they demonstrated. However, in an effort to reduce tensions, Russian colonial authorities ended all anti-cholera measures in the Asiatic District; as a result, the epidemic worsened throughout the city.11

This riot, caused by the circumstances surrounding the cholera epidemic, exposed the distrust on both sides of colonization. The colonized Muslim peoples viewed the outsider Russian colonizers as inflicting death through cholera infection onto them, which resulted in the initial peaceful protest. Russian settlers viewed those that they colonized as outsiders, who stood to upset the social hierarchy that they had imposed and were willing to maintain through violence.

References

1Sahadeo, Jeff. “Epidemic and Empire: Ethnicity, Class, and ‘Civilization’ in the 1892 Tashkent Cholera Riot.” The Slavic Review 64, no. 1 (2005): 117–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3650069.

2Ibid., 119.

3Ibid., 122.

4Ibid.

5Ibid., 122.

7Sahadeo, “Epidemic and Empire.”

8Ibid., 117

9Ibid.

10Ibid., 132.

11Ibid., 137.

Images Cited

1Cacahuate. Modern Map of Central Asia. 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Central_Asia.png#/media/File:Map_of_Central_Asia.png.

2Postcard of Tashkent circa 1910(Почтовая Открытка). 1910. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tashkent#/media/File:Ташкент_пассаж_Ариф-Ходжи.jpg.