Saratov was one of the hardest-hit places in Russia during the 1892 cholera pandemic. From June 15 through August 31, more than 4,400 residents contracted cholera, and 2,270 cholera-related deaths were reported; the death rate per thousand residents in Saratov was 52.6 compare to the 45.8 per thousand throughout the rest of Russia.1 That being said, Saratov was primed for conflict between elites (here, referring specifically to the government, doctors, and police) and common people, as restrictions were imposed on the population.

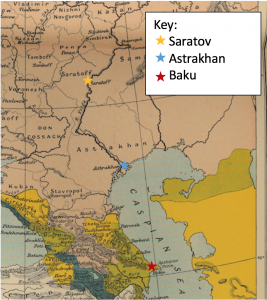

EDITED: Map of the Caspian Sea Region and Caucuses, indicating Major Cholera Cities Referenced1

Part of the mistrust was sparked by official’s failure to act early. As one physician stated, “‘Cholera came to us earlier than we started thinking about it.'”2 Therefore, the number of sick had ballooned before effective measures could be put into place to slow and stop the spread of cholera. Additionally, government officials did not recognize individual cases as an epidemic, meaning that the presence of even the first few cases did not result in any actions being taken.

Some of the measures that city officials enacted included dividing the city into sanitary districts for supervision, closing all small vendors, banning the sale of vegetables, raw fruits, and kvass, and requiring homeowners to wash their homes and wells in a certain way.3 Many homeowners struggled to afford the means of disinfection that they were required to possess, for some because quarantine measures prevented them from working or opening their market stands. Problematically, much of the cholera-prevention instructions were distributed in writing through the newspapers and brochures–this made them nearly impossible to follow for most Saratov inhabitants (particularly the very poor), as may were illiterate.4 These measures, which were difficult for people to familiarize themselves with or to obtain, were enforced on the people by coercion, widening a preexisting rift between the city’s administration and the poor.

Cholera largely infected the poor–in fact, those living in the poorest districts on the outskirts of Saratov faced the highest infection and death rates. Strikingly, “the 60% of Saratov’s population living at the city’s margins accounted for 86% of all cholera cases.”5

Being infected with cholera essentially became a crime, and police often reached brutally to those with the disease. Furthermore, the police were tasked, without training, to disinfect the houses of those who were infected. The combination of their brutality and incompetence resulted in distrust among local populations.6

The brutality, incompetence, and lack of transparency perceived by the general population caused the people to mistrust the elites. This led to the widespread idea that the epidemic had been expressly launched by the government in order to kill off the city’s poor.7 In fact, Saratov inhabitants became convinced that cholera was a poisoning scheme. It became a widespread belief that police and doctors poisoned people with a liquid that they carried around in small bottles to force supposed cholera victims to sniff; it was believed that those who were not killed were then buried alive.8 This belief–and clear indication of deep-seeded mistrust–was so widespread that the local press circulated articles furthering the belief.

Le Cholèra en Russie: Les troubles à Astrakan2

Le Cholèra en Russie: Les troubles à Astrakan2

The Saratov Cholera Revolt ultimately represented the culmination of social tensions and resistance to elite government rule. It began on June 28, when a man, covered in lime, claimed that the police had taken him and attempted to give him cholera; a situation from which he had escaped.9 As a result, people began to fill the streets, and blinded by anger set out to find policemen and doctors. Those who they believed to be a part of either profession were met with violence against themselves and their property, and the protesters also charged into the cholera hospitals, pouring milk and water on the sick, removing them from the facility, and burning the hospital.10

The Saratov riots, resulting from the introduction of novel sanitation procedures and their coercive enforcement, antagonized the tensions between the townspeople and the elites. As a result, the townspeople came to see the elite even more so as outsiders; the very targeted attack against doctors and police officials and their property, without destruction or looting of general businesses, reinforces the idea of a collecting ‘us versus them’ mentality, exposing the gulf between insider and outsider.

References

1Henze, Charlotte E. “Cholera in Saratov, 1892.” In Disease, Health Care, and Government in Late Imperial Russia: Life and Death on the Volga, 1823-1914, 51–96. New York: Routledge, 2011.

2 Ibid., 71.

3 Ibid., 73; Ibid., 84.

4 Ibid., 74.

5 Ibid., 77.

6 Ibid., 75.

7 Ibid., 84.

8Ibid., 87.

9Ibid., 88.

10Ibid., 88.

Images Referenced